Democratization and the Construction of Class Cleavages in Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia, 1992-2019

In this paper, Amory Gethin and Thanasak Jenmana analyze how democratization in Southeast Asia has led to the politicization of social and economic inequalities since the 1990s. Drawing on political attitudes surveys, the authors document how historical legacies, the structure of inequality, and institutional dynamics contributed to differentially structure political cleavages in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines. Ethnic inequalities in Malaysia and regional inequalities in Thailand played a key role in fostering the emergence of strong class divides in these two countries. In Indonesia, by contrast, the rise of new parties mainly used as political vehicles to support their leaders has eroded pre-existing religious and socioeconomic cleavages. The Philippines’ highly unstable party system led to a third trajectory, whereby class divides have been strong, but have lacked the conditions required for their institutionalization and stabilization over time.

Key Findings

- Starting in the 1990s, a number of countries in Southeast Asia saw a wave of democratization that led to the organization of regular and plural elections.

- In Thailand, the victory of Thaksin Shinawatra in 2001 and the redistributive policies implemented during his mandate led to pronounced class cleavages. These cleavages have had an exceptionally strong regional component, with the Northern regions massively supporting Thaksin and his sister Yingluck.

- In Malaysia, the consolidation of the opposition to the National Front has also led to the emergence of class cleavages, as richer Bumiputera and Chinese have been increasingly voting against the ruling coalition.

- In the Philippines, class divides emerged at the end of the 1990s when the candidate Joseph Estrada received massive support from the lower classes. They have declined since then, in a country characterized by one of the highest electoral volatility and instability in the world. In 2016, Rodrigo Duterte was elected president thanks to an unprecedented coalition between the urban middle class and voters living in the island of Mindanao.

- In Indonesia, the emergence of new parties and the rising personalization of power have been associated with a gradual decline of preexisting religious and class cleavages, although religious minorities continue to display significant support for the secular-nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle inherited from founding father Sukarno.

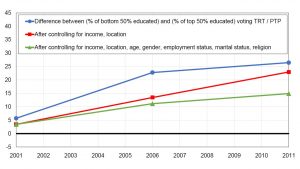

Figure: The educational cleavage in Thailand

The figure shows the difference between the share of bottom 50% educated voters and the share of top 50% educated voters voting for the Thai Rak Thai, the Pheu Thai, and other pro-Thaksin parties, before and after controls. In 2001, bottom 50% educated voters were 6 percentage points more likely to vote for these parties, compared to 26 percentage points in 2011.

Contacts

Authors

- Amory Gethin (Paris School of Economics, World Inequality Lab): Amory.gethin@psemail.eu

- Thanasak Jenmana (Paris School of Economics): thanasak.jenmana@psemail.eu

Media inquiries

- Olivia Ronsain: olivia.ronsain@wid.world; +33 7 63 91 81 68

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Clara Martínez-Toledano, Thomas Piketty, Dirk Tomsa, and Andreas Ufen for their useful comments.